She can fly

I don’t remember how I found my way to Rhiannon Giddens. I think I came across her song “We Can Fly” somehow and was so impressed (more on that later) that I futzed around the internet and found myself drawn into the world of an artist who has been around for decades and whom I had never heard of.

I’m not a musician, singer, songwriter, critic, or music scholar. (She is all of those things, and more.) This essay is not an analysis of her musical ability, her discography, or her biography. I haven’t listened to everything she’s sung, written, or said. It’s more of me sitting on the ground picking the petals off a daffodil and saying, “I like this. I like this not.” Except that with Giddens, it’s more of “I like this. And I like this. And I’ll probably like that, too.”

Here are 10 of her songs that I like (there are others), followed by a description of some of the other work she is doing. You can click on the graphics to hear (and see) her perform.

Leaving Eden

Laurelyn Dossett, who wrote “Leaving Eden,” is a native North Carolinian and singer/songwriter, like Giddens. This is a haunting song about mills closing and poor families forced to migrate for work: “A hard life full of working/With nothing much to show/A long life of leaving with nowhere to go.” I found a video of Dossett and Giddens singing together, which makes the song even better.

No work for the working man, Just one more empty mill. Hard times for working men, Hard times, harder still. The crows are in the kitchen, The wolves at the door. Our fathers’ land of Eden is paradise no more. My sister stayed in Eden. Her husband’s got some land. An agent for the county thinks that they might make a stand. A hard life full of working, With nothing much to show, A long life of leaving with nowhere to go.

Pretty Bird

Hazel Dickens wrote “Pretty Bird” in 1972. She was a coal miner’s daughter, well-versed in union struggles, and a pre-eminent bluegrass singer/songwriter. “I envied the little bird sitting on the high wire,” she said. “It could fly away at any given moment and be free.” Like Dickens, Giddens sings the song a cappella and captures the soaring, heartrending vocal style that Dickens represented.

I cannot make you no promise, Love is such a delicate thing. Fly away, little pretty bird, For he’d only clip your wings. Fly, fly away, little pretty bird, Fly, fly away. Fly away, little pretty bird, And pretty you’d always stay.

No Man’s Mama

This song was written by two Jewish songwriters, Lew Pollack and Jack Yellin, who also wrote “My Yiddishe Mama.” Ethel Waters recorded it in 1925. It was pretty risqué for its time.

I'll tell you there was a time I used to think that men were grand. No more for mine, I've gone and labeled my apartment “No Man’s Land.” Am I makin’ it plain? I will never again Drag around another ball and chain, Because, I'm no man’s mama now.

Hold on to your seat. This is going to put a smile on your face.

They’re Calling Me Home

Alice Gerrard, Dickens’ musical partner, wrote “They’re Calling Me Home.” She said she has a soft spot for lonesome songs. This one certainly qualifies. It’s interesting because it is from the point of view of someone who is dying. I like Giddens’ interpretation. Maybe it’s her opera training that enables her to sing long phrases in a single breath, like “But I miss my friends of yesterday/Oh, they’re calling me home.” Like “Pretty Bird,” this song is stripped down to its essentials.

My time has come to sail away. I know you’d love for me to stay, But I miss my friends of yesterday. Oh, they’re calling me home, They're calling me home. I know you'll remember me when I'm gone, Remember my stories, remember my songs, I'll leave them on Earth, sweet traces of gold. Oh, they’re calling me home, They’re calling me home.

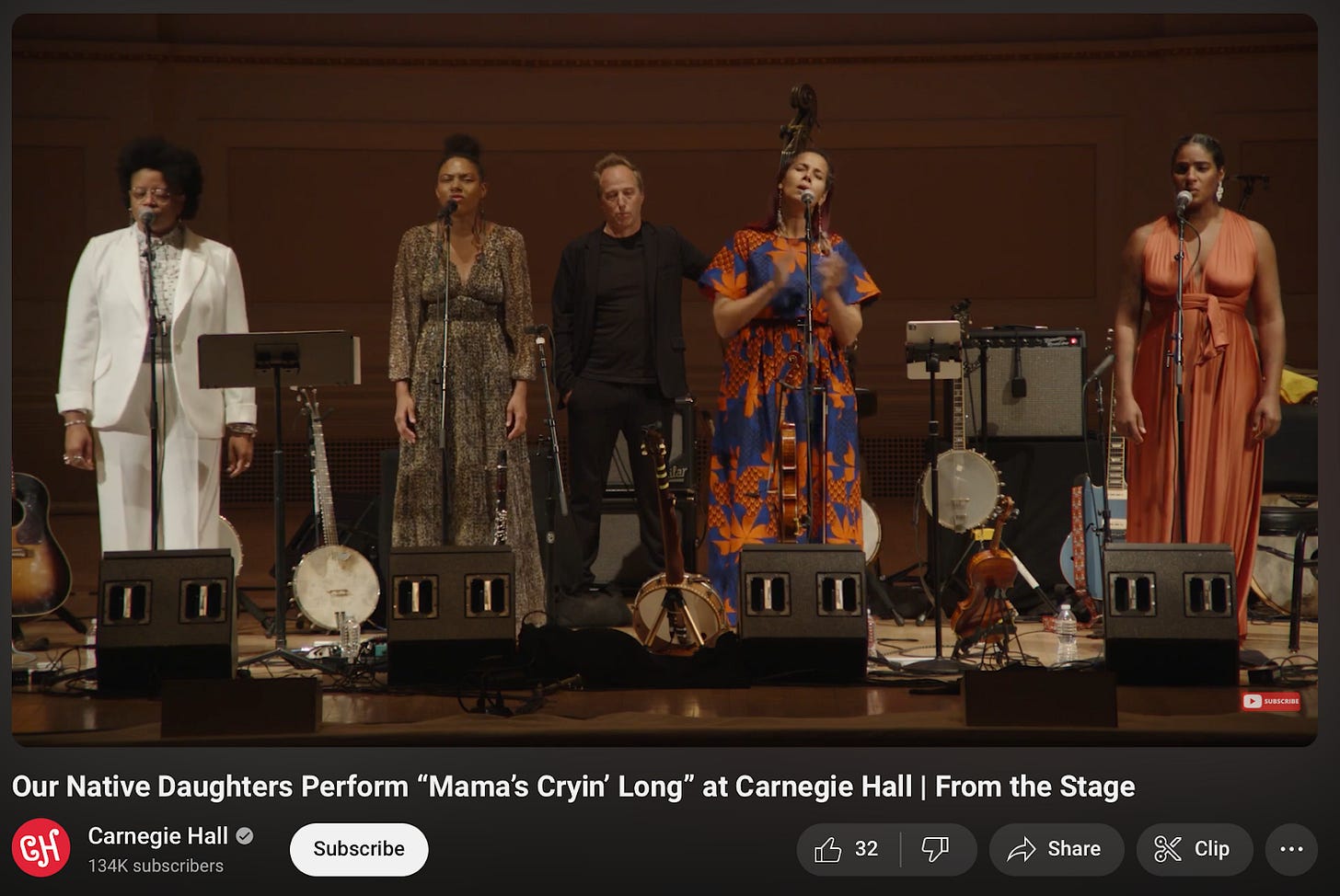

Mama’s Cryin’ Long

“Mama’s cryin’ long” is from Songs of Our Native Daughters, the liner notes for which explain:

Songs of Our Native Daughters shines new light on African American women’s stories of struggle, resistance, and hope. Pulling from and inspired by 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century sources, including narratives of enslaved people and early minstrelsy, kindred banjo players Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, and Allison Russell reinterpret and create new works from old ones. With unflinching, razor-sharp honesty, they confront sanitized views about America’s history of slavery, racism, and misogyny from a powerful, Black female perspective.

Giddens wrote this song, from a child’s point of view, about an enslaved woman rising up against her oppressor. This harrowing a cappella song is a call-and-response backed by a percussive rhythm.

Mama’s cryin’ long (And she can't get up) Mama’s cryin’ long (And she can't get up) Mama's hands are shakin’ (And she can’t get up) Mama's hands are shakin’ (And she can’t get up) It was late at night (When she got the knife) It was late at night (When she got the knife) She went to his room (When she got the knife) She went to his room (When she got the knife) Mama’s dress is red (It was white before) Mama’s dress is red (It was white before) Lift it up and see (It was white before) Lift it up and see (It was white before)

Factory Girl

“Factory girl” is a traditional Irish song about a wealthy young man who wooes a beautiful young woman. In one version she refuses his offer of marriage and sends him on his way, saying she is a factory girl. In another version she marries someone richer than he.

Now this maid she’s got married, become a great lady, Became a rich lady of fame and renown. She may bless the day and the bright summer’s morning. She met with the squire and on him did frown. It’s now to conclude and to finish those verses: lt’s may they live happy and may they do well. Come fill up your glasses and drink to the lasses That attend the sweet sound of the factory bell.

Giddens rewrote the ending after learning of the collapse of a building in Dhaka, Bangladesh in April 2013 that housed several garment factories. The collapse killed more than 1,000 — mostly young women — and injured 2,500. It was the worst disaster in the worldwide garment industry.

The crowd gathered ‘round, couldn’t hide the destruction. I cast my eyes on it in such disbelief. A truth of the world settled into the ashes, The rich man’s neglect is the poor man’s grief. As I stood there a whisper it did caress me, A faint scent of roses my senses begun. I lifted my face and I saw that above me, A thousand young butterflies darkened the sun.

We Could Fly

Giddens wrote this song with Dirk Powell, and then worked with artist Briana Mukodiri Uchendu to turn it into a book and a video.

Mama, dear mama, come and stand by me. I feel a lightness in my feet, a longing to be free. My heart it is a-shakin’ with an old, old song, I hear the voices sayin’ it’s time for moving on. She took her mama by the hand, they rose up in the air. They held each other tight and then They flew away from there. They held each other tight and then they flew away from there. They could fly, they could fly. They could slip the bonds of earth and rise so high. They could fly across the ocean, Together, hand in hand, Searching, always searching for the promised land.

When I write the Great American Novel about the struggles of two women (who might just be based on my mother and grandmother), and that novel becomes a best-seller and wins a Pulitzer, and then it gets optioned for a movie, and then I am asked to write the screenplay, and then the director and producer ask me what the film’s theme song should be, I will answer “We could fly” by Rhiannon Giddens.

Wrong Kind of Right/You’re the One

I enjoyed these two love songs. “Wrong Kind of Right” has a Motown-ish feel. When you listen to it, imagine Giddens’ back-up singers responding to Giddens’ call (“I’m just the wrong kind of right”) with “The wrong kind of right.” An updated version of Diana Ross and the Supremes.

I woke up this morning, Something on my mind. I’m lying here beside you, But I feel so far behind. I remember the time, There used to be an open door. Now what I say, Is not what you wanna hear anymore. I’m just the wrong kind of right, Wrong kind of right, I’m just the wrong kind of right, Wrong kind of right.

You’re the One has more of a country/pop flavor, and the banjo-and-fiddle intro makes that point.

I never knew Life could be so wonderful, That there could be someone Who was so beautiful. And I never knew That I could be so free To love someone like you, and I wanna love you forever. And I’ll be with you For worse and for better. And I never thought I’d fall, But you’re the one.

Another Wasted Life

Kalief Browder was arrested when he was 16 years old and falsely accused of stealing a backpack. He spent nearly three years of torture (including starvation, beatings, refusal of medical care, and 800 days of solitary confinement) in Rikers Island and was released without charge in 2013. On June 6, 2015, 12 days after his 22nd birthday, he committed suicide.

Rhiannon Giddens wrote “Another Wasted Life” in response to that horror. She also worked with the Pennsylvania Innocence Project to produce a memorial video, which includes 22 men who collectively had spent more than 500 years in prison for crimes they did not commit. Giddens talked with Democracy Now! about her song: “It was not only how [Browder] was treated — an innocent teenager put through the system in such a brutal way, but … I felt that his life was stolen from him,” she said. “Not only the hours that he had to spend inside enduring what he had to endure, but also the hours that he never got to live. That just kind of went all over me and I just sat down and wrote it.”

American Railroad

In 1998 the renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma founded Silkroad, “a collective of artists from around the world who create music that engages their many traditions.” When Giddens joined Silkroad as artistic director in 2016, the first project she proposed was “American Railroad,” an exploration of the intermingling of music created by the Indigenous peoples (whose land was stolen for the rights-of-way), and the immigrant workers who laid the track.

Profit-seeking corporations and the American government financed [the Transcontinental Railroad], but the people who actually built it and who were most affected by it are the focus of this program of music — Indigenous and African Americans as well Irish, Chinese, Japanese, and other immigrant laborers whose contributions have been largely erased from history. Silkroad’s American Railroad seeks to right these past wrongs by highlighting untold stories and amplifying unheard voices from these communities, painting a more accurate picture of the global diasporic origin of the American Empire.

On the American Railroad website, watch the 5.5-minute video of the project (about halfway down the page), which features some of the musicians Giddens brought together for this project.

And also

Giddens has done dozens of educational videos and programs, including one on the history of the banjo, and Aria Code, an NPR podcast “that pulls back the curtain on some of the most famous arias in opera history.” She has won two Grammys and was nominated for eight more. She was awarded a MacArthur “genius grant” and a Pulitzer Prize for her opera “Omar,” based on the life of West African scholar Omar Ibn Said, who was captured and sold into slavery in South Carolina. Wikipedia lists 41 awards and nominations. She is a recurring cast member on the TV show “Nashville,” and had cameos in “Parenthood” and “Nurse Jackie” and in the film “The Great Debaters.” She seems to be touring and lecturing all the time. Oh, and she played banjo and viola on Beyoncé’s song, “Texas Hold ’Em”.

Culture is one of the ways in which humans adapt to our environments. But we are one species. Race, class, gender, sexual orientation, national origin, and ability are social constructs that transform variation within the species into differences in relation to political and economic power. From an evolutionary point of view, there is only one “culture” as an adaptive mechanism. Variations in culture reflect adaptations to different natural and social environments, which change over time. When variations in culture are subsumed within social constructs of race, class, national origin, and gender, these variations become hierarchies of differences — some cultures (e.g., White, European) are “better” than other cultures (e.g., everyone else).

Giddens is dismantling those hierarchies, and spreading her good news in the process.

Rhiannon Giddens is a polymath — an historian, musicologist, cultural critic, musician, public intellectual, people’s artist, teacher, singer/songwriter, and performer. She moves easily among musical genres but keeps one foot in the old-time and African American roots music of her North Carolina foothills. She is interested in everything, and if she couldn’t share her joy and love and artistry with people everywhere, I think she would just burst.