Inherit the Wind

I was probably in my teens when I first saw the film Inherit the Wind. The film, directed by Stanley Kramer and released in 1960, was based on a play written by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee (no, not that one) and first staged in 1955. (The play was adapted to the screen by Nedrick Young and Harold Jacob Smith.)

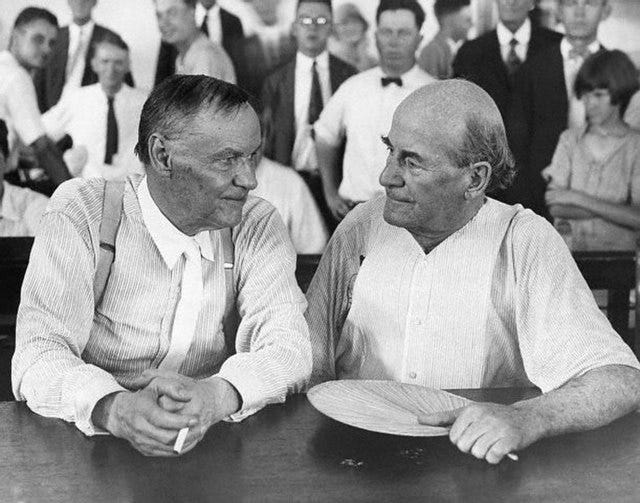

At first glance the subject matter seemed to be the Scopes Trial of 1925 in Dayton, Tennessee. The state legislature had passed a law outlawing the teaching of evolution in public schools. The ACLU wanted to challenge the law, and John T. Scopes, a teacher, agreed to be arrested for having evolution material in the classroom. William Jennings Bryan, an evangelical populist and a three-time presidential candidate, and Clarence Darrow, a renowned first-amendment and labor lawyer, were the prosecutor and defense attorney, respectively. The trial made international headlines. Bryan died five days after the trial ended.

Some years later when I fell in love with evolutionary theory, I learned that the 1925 trial differed substantially from the trial presented in the movie. And when I realized that the film was made in the late 1950s, in the midst of the Red Scare, I wondered whether the film’s sharp critique of group-think and censorship might have been a reaction to the anticommunist hysteria of that time. That was indeed the case. I found an article in the Topeka Capital-Journal from 2001:

“We used the teaching of evolution as a parable, a metaphor for any kind of mind control,” Lawrence told Newsday for a story on the 1996 Broadway revival of the play. “It’s not about science versus religion. It’s about the right to think.”

Just as Arthur Miller looked to the 17th century Salem witch trials to make his anti-McCarthyism statement in [his 1953 play,] “The Crucible,” Lawrence and Lee found their vehicle in Scopes. “We thought, ‘Here's another time when there was a corset on your intellectual and artistic spirit,’” Lawrence said.

Kramer’s film grossed $2 million and lost $1.7 million.

Spencer Tracy and Frederick March star as Henry Drummond (the Clarence Darrow character) and Matthew Harrison Brady (the William Jenings Bryan character). Gene Kelly plays E.K. Hornbeck, modeled after H.L. Mencken, the acerbic critic who covered the 1925 trial for the Baltimore Sun. John Scopes’ character is Bertram Cates, played by Dick York (who a few years later would co-star with Elizabeth Montgomery in the TV series “Bewitched”). Leslie Uggams sings both the intro and the outro.

The two principal women characters are Cates’ fiancee Rachel Brown (Donna Anderson), who is the daughter of a fanatical preacher, and Brady’s wife Sarah (Florence Eldridge). Both are excellent. But the film is built around the confrontation between Drummond and Brady and most of that struggle takes place in the courtroom.

The cast (and the town of “Heavenly Hillsboro”) is entirely White. Early on in the film, Rachel visits “Bert” in jail and is greeted by the bailiff, who has been playing cards with the prisoner. She asks the bailiff whether Bert is okay. He responds, “Well, of course he’s … the safest place in the world is in a jail.” 1925. Tennessee. Yeesh. I can imagine a White bailiff of that time and place saying that to a White woman, but I couldn’t figure out whether the writers meant that as a poke at segregation.

Spencer Tracy gives an astounding performance as a lawyer whose frumpy, disheveled appearance belies a sharp mind and an even sharper tongue. He was nominated for the best-actor Oscar, but the award went to Charlton Heston for Ben Hur. Tracy won that Oscar the next year for Judgment at Nuremberg.

March plays Brady as somewhat of a boob, but the script portrays Brady that way; I think the authors were on Drummond’s side and March’s character was more of a foil for Tracy’s character. In any case, March was magnificent.

I have watched Inherit the Wind many times and thought about it even more.

Here are my three favorite scenes.

In the first scene, the judge disqualifies the scientific experts that Drummond called to testify as to the evidence for evolution. Drummond gets fed up, says that the town has already found his client guilty, and asks to be removed from the case. Brady berates Drummond for implying that the town’s “expression of an honest emotion will in any way influence the Court’s impartial administration of the law.” Drummond responds:

“I say that you cannot administer a wicked law impartially. You can only destroy. You can only punish! And I warn you, that a wicked law, like cholera, destroys everyone it touches! Its upholders as well as its defiers!

“Can't you understand that if you take a law like evolution and make it a crime to teach it in the public schools, tomorrow you can make it a crime to teach it in the private schools? And tomorrow you may make it a crime to read about it? And soon you may ban books and newspapers. And then you may turn Catholic against Protestant, and Protestant against Protestant, and try to foist your own religion upon the mind of man! If you can do one, you can do the other! Because fanaticism and ignorance is forever busy and needs feeding. And soon, Your Honor, with banners flying and drums beating we'll be marching backward — BACKWARD — to the glorious ages of that sixteenth century when bigots burned the man who dared bring enlightenment and intelligence to the human mind!”

In the second scene, Drummond maneuvers Brady into admitting that the Bible is open to interpretation. When Brady asks Drummond whether he believes in anything holy, Drummond responds:

“Yes. The individual human mind. In a child’s power to master the multiplication table there is more sanctity than in all your shouted ‘Amens!’ ‘Holy, Holies!’ and ‘Hosannahs!’ An idea is a greater monument than a cathedral. And the advance of man’s knowledge is more of a miracle than any sticks turned to snakes, or the parting of waters!”

Drummond asks Brady — does a sponge think? If God wants a sponge to think, Brady responds, it thinks. Drummond points at Bertram Cates:

“This man wishes to be accorded the same privilege as a sponge! He wishes to think!”

The third scene is the film’s ending, which features Drummond and Hornbeck. The latter dismisses Brady as “that Bible-beating bunco artist.” Drummond berates Hornbeck for his cynicism:

“You never pushed a noun against a verb except to blow up something.”

And laments Brady’s death:

“A giant once lived in that body, but Matt Brady got lost because he looked for God too high up and too far away.”

On occasion the script is pretty close to the dialog between Darrow and Bryan during their courtroom battle.

On the seventh day of the trial, Darrow questioned Bryan about the date of the biblical flood:

Darrow: But what do you think that the Bible, itself, says? Don’t you know how [the age of the Flood] was arrived at?

Bryan: I never made a calculation.

Darrow: A calculation from what?

Bryan: I could not say.

Darrow: From the generations of man?

Bryan: I would not want to say that.

Darrow: What do you think?

Bryan: I do not think about things I don’t think about.

Darrow: Do you think about things you do think about?

Bryan: Well, sometimes.

Bryan and Darrow got into it a couple of times when Bryan accused Darrow of ridiculing Christians:

Bryan: The purpose is to cast ridicule on everybody who believes in the Bible, and I am perfectly willing that the world shall know that these gentlemen have no other purpose than ridiculing every Christian who believes in the Bible.

Darrow: We have the purpose of preventing bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the education of the United States and you know it, and that is all.

…

Bryan: Your honor, I think I can shorten this testimony. The only purpose Mr. Darrow has is to slur at the Bible, but I will answer his question. I will answer it all at once, and I have no objection in the world. I want the world to know that this man, who does not believe in a God, is trying to use a court in Tennessee…

Darrow: I object to that.

Bryan: (Continuing) to slur at it, and while it will require time, I am willing to take it.

Darrow: I object to your statement. I am exempting you on your fool ideas that no intelligent Christian on Earth believes.

And then there was this cringeworthy exchange (which did not make it into the film) in which Darrow objected to Bryan recalling what a Buddhist in Rangoon, Burma told him about Buddhism:

Darrow: If Your Honor please, instead of answering plain specific questions, we are permitting the witness to regale the crowd with what some black man said to him when he was traveling in Rang–who, India?

Bryan: He was dark-colored, but not black.

The tension between Darrow and Bryan is palpable in the transcript. It’s difficult to sense from the transcript whether they yelled at each other, but Drummond and Brady sure do in the film. Of course, the courtroom in the film is only the backdrop for the clash of these two men, so the writers were free to heighten the drama by turning up the volume. Kramer kept Tracy and March in the frame for much of the time that Drummond was interrogating Brady. The camera goes in tight on Drummond when he says the most important line of the film: “Because fanaticism and ignorance is forever busy and needs feeding!”

The legislation that led to the Scopes Trial was one of many that sought to make teaching evolution a crime. By the 1970s and 1980s, the anti-evolution crowd realized that trying to get evolution out of the public schools was not working, so they changed tactics: instead of trying to replace evolution with Christian fundamentalism, they relabelled their product “creationism” and argued that “creation science,” or “intelligent design,” should be taught along with evolution. Even after federal courts and the Supreme Court dismissed that argument, the fight continues. West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice just signed into law a bill that would allow teachers to discuss “other theories” of evolution. Some states are using school voucher programs to allow parents to use public money to send their kids to religious schools that teach creationism.

Inherit the Wind is streaming on Amazon Prime Video.