Autism isn't profitable

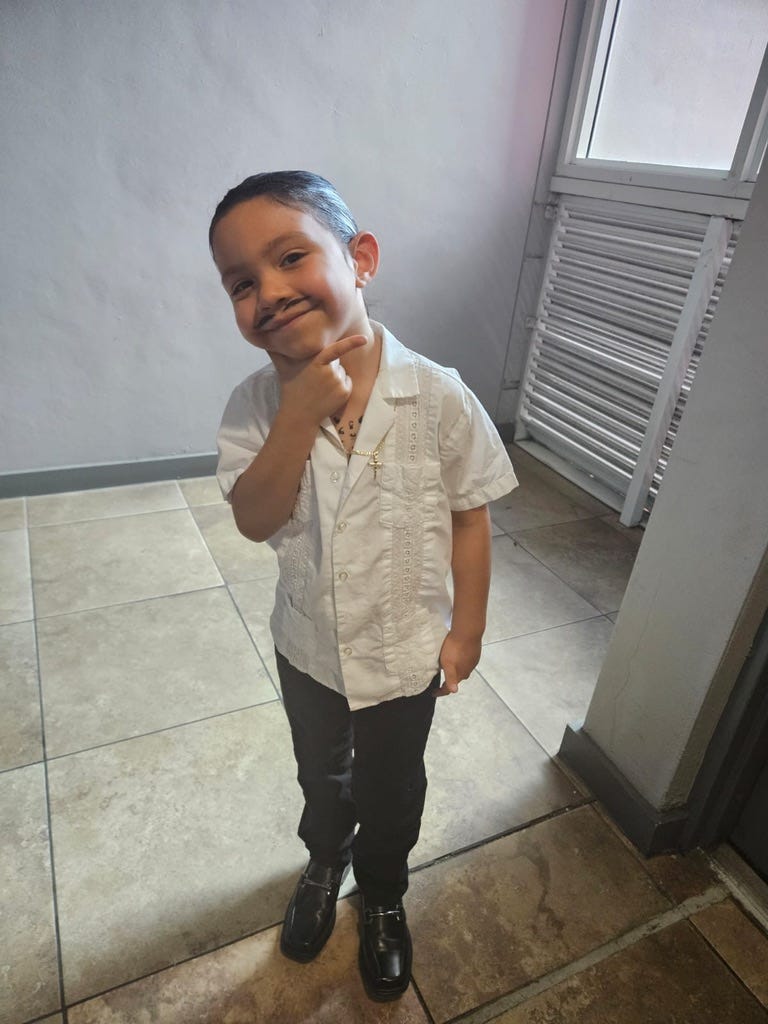

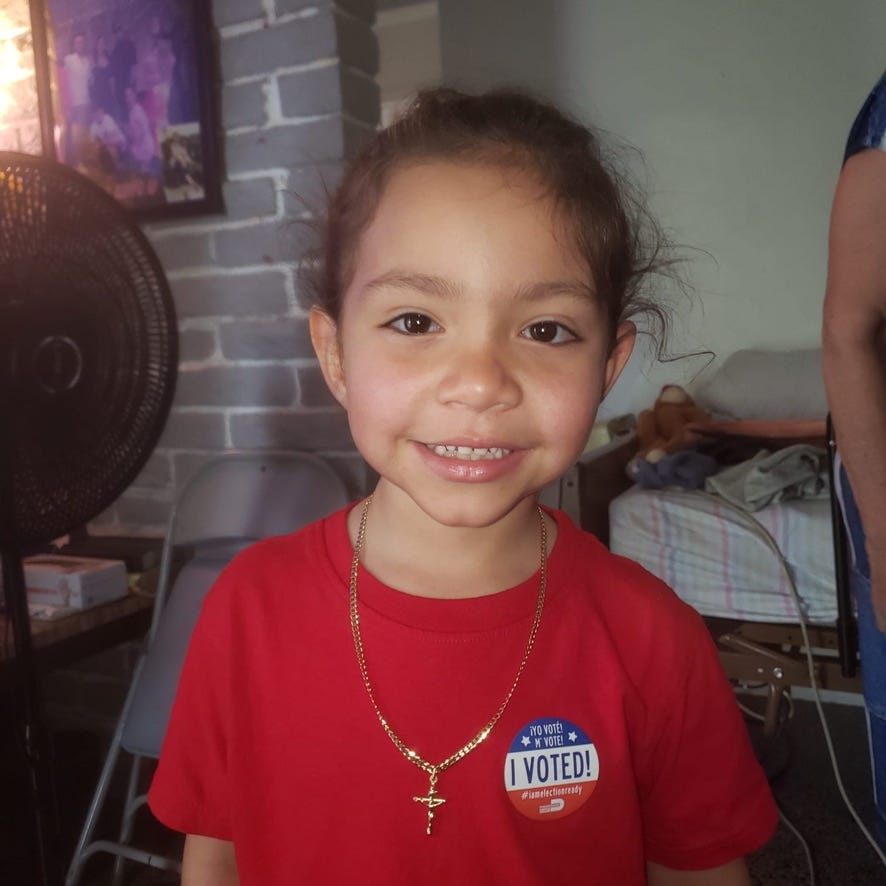

My youngest grandson, Aydrien, who turns 6 years old this month, is autistic. His mom, Cristina Rivera, my older daughter, has struggled to get him the services he needs, both general pediatric services and behavioral health care, and is his fiercest advocate with school, medical, and behavioral health personnel. His dad, Sandro, is a long-haul truck driver on the road two to three weeks at a time, and the family relies on his salary to make ends meet. Being a mom is a full-time job; being a mom of an autistic child is a 48-hour-a-day job. On top of which, she is homeschooling Aydrien because of a conflict with the administration at his former elementary school. I am so proud of her.

Cristina has met other mothers of autistic children, some of whose stories are heartbreaking; for example, a single mother of two autistic children, each of whom has particular therapeutic needs. The mom has to work two jobs, which means she has less time than Cristina has to be part of the process and to advocate for her children.

Until recently, Aydrien had been in self-contained classrooms (in which the children are on the autism spectrum). He receives behavioral therapy four days a week from a registered behavioral technician, who is supervised by a board-certified behavioral analyst. He also receives speech and occupational therapy weekly. This attention to his needs has brought about astonishing progress in his ability to communicate. He is also remarkably smart. This might sound like grandpa boasting, but experts confirm my observation. Those same experts have determined that he needs this amount and these kinds of therapy to help him develop the skills to manage his autism. Less therapy would be really bad for him.

ProPublica published an investigation entitled “UnitedHealth Is Strategically Limiting Access to Critical Treatment for Kids With Autism.” The insurance company manages Medicaid behavioral therapy programs for a dozen states (not including Florida, where we are). ProPublica found that, since the federal Medicaid program began covering behavioral services, “the number of children diagnosed with autism has ballooned; experts say greater awareness and improved screening have contributed to a fourfold increase in the past two decades — from 1 in 150 to 1 in 36.” Which has led UnitedHealth, through its Optum subsidiary, to cut costs by denying coverage to patients and dropping agencies that provide services. “It is part of a secret internal cost-cutting campaign,” ProPublica said, “that targets a growing financial burden for the company: the treatment of thousands of children with autism across the country.”

The investigation highlighted the struggle of Sharelle Menard, a single mother of a severely autistic son, Benji, in south-central Louisiana, to get and maintain the intensive therapy her son needs. When the agency that provides behavioral therapy documented that Benji needed 33 hours of therapy a week, Optum told Menard, “Your child has been in [applied behavioral analysis therapy] for six years. After six years, more progress would be expected.” So Optum cut the amount of therapy.

Experts interviewed by ProPublica denounced that decision as naked cost-cutting that ignores the standard of care for behavioral health, which recognizes that each patient progresses at their own pace.

When the agency documented that fewer hours of therapy resulted in Benji regressing behaviorally, they decided to provide the needed therapy at their own cost and to sue UnitedHealth.

Asked by ProPublica for comment, UnitedHealth responded:

In an email, a spokesperson said “we are in mourning” [because of the murder of its CEO] and could not engage with a “non-urgent story during this incredibly difficult moment in time.” Offered an additional day or two, the company would not agree to a deadline for comment.

In another investigation, ProPublica related that Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Texas denied intensive outpatient care to Geneva Moore, a mental health patient, because “you have made progress” and “you are not a danger to yourself or to others,” even though her therapist explained that such therapy was necessary to maintain that progress.

“The biggest concern was the abnormal thoughts — the suicidal ideation, self-harm urges — and extensive trauma history,” the therapist recalled in an interview with ProPublica. “I was really trying to emphasize that those urges were present, and they were consistent.”

During her final day at the program, records show, Moore’s suicidal thoughts and intent to carry them out had escalated from a 7 to a 10 on a 1-to-10 scale. She was barely eating or sleeping.

A few hours after the session, Moore drove herself to a hospital and was admitted to the emergency room, accelerating a downward spiral that would eventually cost the insurer tens of thousands of dollars, more than the cost of the treatment she initially requested.

This week Cristina received a letter from the State of Florida stating that Aydrien’s behavioral analysis services, which are now covered directly through Florida Medicaid, will transition in February to privately-run health plans supervised by Florida Medicaid. So now she has to worry whether the agency she is using now, which she is happy with, will be in-network, and whether the therapy that Aydrien needs will conflict with the profits the shareholders expect.

Taking the profit motive out of healthcare, making healthcare free and universal, is necessary but not sufficient. Even with such healthcare, Sharelle Menard and Cristina would still be the primary caregivers of their children. That’s a lot of work, a lot of unpaid labor, which falls disproportionately on women, especially women of color. And my son-in-law Sandro should not be forced to choose between making a living to support his family, and participating fully with Cristina in caring for Aydrien. We need a society that values children and the people who take care of them.

Department of Correction: In last week’s newsletter, I wrote that the rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem occurred in 164 AD. Nope. 164 BCE. This is what happens when you don’t have an editor.