Miss You, Dad

In the Fall of 1968, the United Federation of Teachers, led by Albert Shanker, went on strike against Black parents struggling for community control of the schools in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn. The union membership was overwhelmingly white and majority Jewish. Instead of looking for ways to work with the community to address the institutional racism in the public education system, Shanker cried “Black antisemitism” and politicians (of both parties) and the media whipped the charge into a hysteria. Antisemitic acts by individuals in the community were well-publicized, but the struggle for community control of the schools had nothing to do with antisemitism, and Jewish teachers and activists were part of that struggle. (School Colors, Episodes 2 and 3, is a good introduction to what happened.)

My family is pro-union. Mom and Dad didn’t sit my sisters and me down and explain the importance of unions. We breathed it in. Some things you just don’t do — you don’t talk back to adults, you don’t treat people unfairly, and you don’t cross a picket line.

I crossed a picket line, with my parents’ permission.

That fall I was in 11th grade at Stuyvesant High School on East 15th Street in Manhattan. Teachers were picketing outside the school, which was locked. A bunch of us students and a few teachers opposed to the strike broke into the school and held “classes” for a couple of days before we were told we were trespassing.

I wanted to be a biologist. Louis Pasteur was a hero to me. Cell biology was almost as fascinating to me as girls, and a lot less scary. One of the leaders of the striking teachers was Mr. Linder, a biology teacher. He saw me break into the school. After the strike ended, I had him for biology. During class on December 4, some of us students booed an announcement on the P.A. system. Mr. Linder went red with anger, called me out, told me to stand in a corner, threatened to put a mark on my Delaney card, and demanded that I bring a note from my parents as proof that I told them about my disruption.

I related the event to Mom and Dad that evening. They agreed that he would write a letter and she would type it up. The letter we have in the family archive is a copy of the original; I can tell that Mom used carbon paper between two sheets of letter paper.

I didn’t read the letter before I gave it to Mr. Linder the next day. I think I didn’t want to read Dad’s criticism of me. I watched Mr. Linder’s face turn red as he read the letter. Then he folded the letter, put it back in the envelope, gave it back to me, and walked away.

I read the letter after class and smiled. Dad had my back. Always.

On December 2, 1996, almost 28 years to the day from his defense of his son, I presented my eulogy at Dad’s funeral:

Some glory in their birth, some in their skill, Some in their wealth, some in their body’s force, Some in their garments, though new-fangled ill, Some in their hawks and hounds, some in their horse, And every humour hath his adjunct pleasure, Wherein it finds a joy above the rest: But these particulars are not my measure, All these I better in one general best. Thy love is better than high birth to me, Richer than wealth, prouder than garments’ cost, Of more delight than hawks or horses be, And having thee, of all men’s pride I boast. Wretched in this alone, that thou may’st take All this away and me most wretched make.

My father would not speak about himself. He never spoke about himself in the 43 years I knew him. Yet if he had spoken about that which was important to him, he might have echoed Shakespeare's 91st sonnet, although he would have, as he was wont to say, translated it into English.

I think that if you had asked him when he was a young man what he wanted to be when he grew up, he would have said, “a husband and a father.” That was his natural state and being a bachelor and childless was just a temporary condition. It was not that he had something to prove, it was that he had so much to give.

And he gave so much to his children. My father taught without teaching. When he washed the dishes or swept the floor or set the table, we learned that marriage is a union of equals. When he used tape and staples to patch his clothes rather than buy new ones, we learned that the family comes first. (Of course, I'm older now and I do set priorities, but I still will not use tape, it's too tacky.) His passion for knowledge taught us the value of education. His commitment to justice taught us that we are our brother’s keeper. He was a serious man, but sometimes he acted so silly. He helped us with our homework and he drew funny cartoons. He was happiest when we were all together. I think he must have cried when we moved away.

Someone once said, “You must become the change you want to make.” My father lived what he believed. From the union organizing drive at the Army Proving Grounds at Aberdeen, Maryland during World War II to the union organizing drive at his last job at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich in New York City, my father was never afraid to speak his mind, even if what he had to say was unpopular. Sometimes the cost was high: he was teaching mathematics in a Baltimore high school during the McCarthy era when the local witch hunters decided to make an example of him to anyone who dared to think un-American thoughts. Newspaper headlines railed against this “communist” in the public schools. He was forced to leave Baltimore. It was a hard time.

Fortunately, he came to New York City, where he immediately fell in love with my mom, of course. So in the end, the witch hunters did not attain their goal. Where there was just one of him, the one became two, the two produced three, the three married three others and produced five.

They tried to get rid of one, now there are 13. If they had known what would happen, they might have promoted him to principal.

He lived what he believed. He had an unshakable, incorruptible faith in the human spirit. He refused to reduce human relationships to “what's it going to cost me?” His heart had room for millions of people and he spent a lifetime tending to the souls entrusted to his care. Sometimes an empathetic ear, sometimes a picket line, sometimes addressing envelopes, sometimes a march through a rain of bricks and bottles — he did what was necessary for the people in his heart. He did not love causes, he loved people.

As the years passed, he worried about the effect of his failing health on his family. In 1983 he wrote a letter to my mother, which he filed among the family papers. “Norma,” he began, “if I don't make it…” What followed was a list of “remember-to’s” including taking care of his sister [Mariam], who had just come through a horrible ordeal at the hands of a malpracticing doctor; paying the quarterly real estate taxes and HMO premiums; disconnecting, draining and storing the garden hose for winter; resetting the thermostat for daylight savings time; and checking the furnace every week during winter and about once a month in summer.

“Most important of all,” he ended his letter, “I love you and the kids and their loved ones and Mariam and my best to all our wonderful friends. I am sorry for the hard times I caused you and I know you reciprocate, but overriding all that — we had a wonderful relationship, witness the wonderful children we have. I am glad our lives intertwined; much of the meaning in my life derived from the values and important work in your life. I hope you will carry on, bravely and constructively, as always.”

Sounds like Shakespeare to me, translated into English.

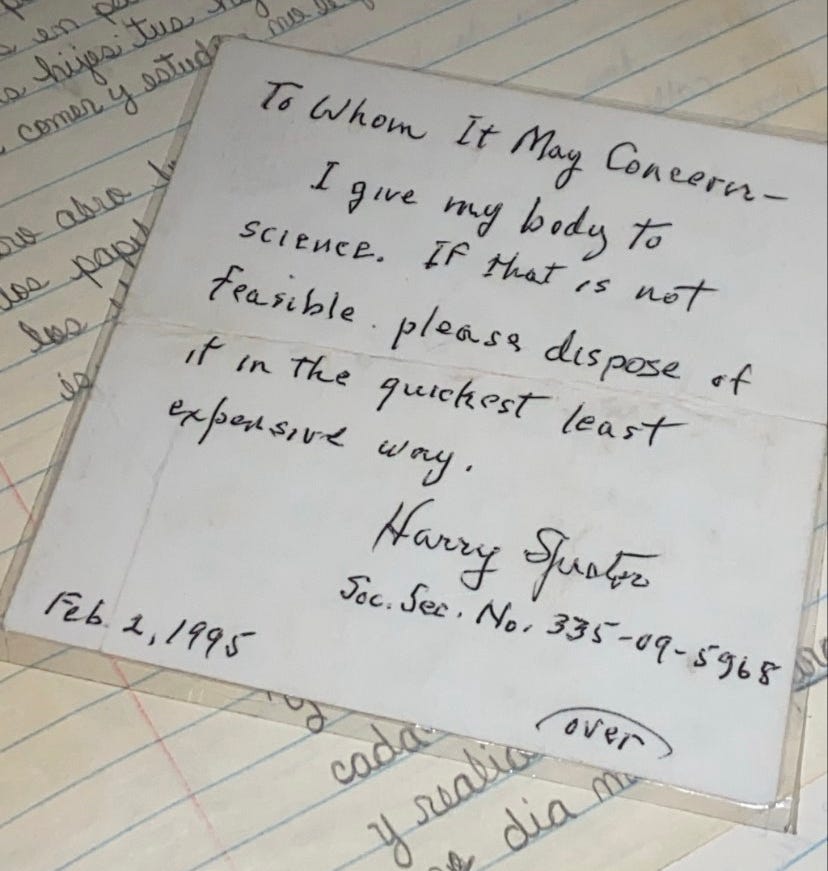

On February 2 of last year, perhaps at a moment when he felt his health was particularly delicate. he wrote a note to us on a slip of paper. On one side, “To Whom It May Concern — I give my body to science. If that is not feasible, please dispose of it in the quickest, least expensive way.” Typical of my father.

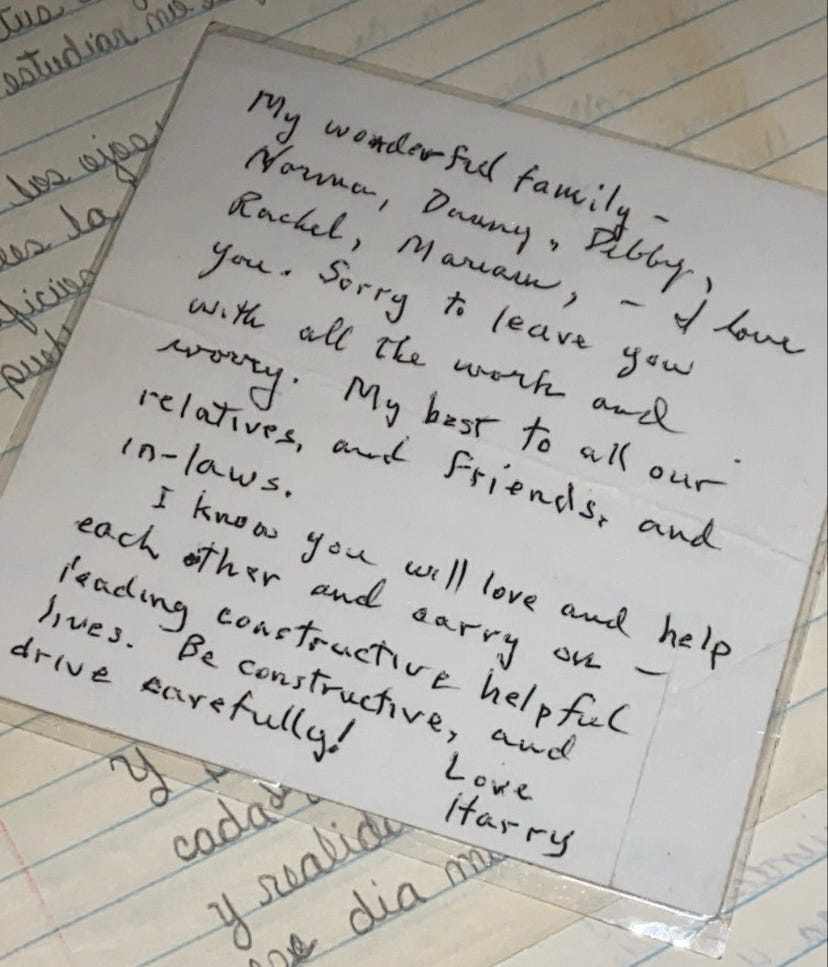

On the other side, “My wonderful family — Norma, Danny, Debby, Rachel, Mariam — I love you. Sorry to leave you with all the work and worry. My best to all our relatives and friends and in-laws. I know you will love and help each other and carry on leading constructive, helpful lives. Be constructive, and drive carefully!” Also typical of my father.

We and he did not know the cause of his failing health. He and his doctors attributed it to congestive heart failure. But it was cancer. By the time we became aware of the problem, the cancer had consumed too much of him.

He never complained. He did not become bitter or angry. He asked for nothing for himself. As he lived, so he died, at peace with himself, surrounded by his family.

My father was the tallest tree in our forest, its roots secure in past and family. His gentle kindness sheltered us and all who came seeking friendship, counsel, or an empathetic heart. He was a giving tree. He was the tree of Psalms 1:3, “planted by the rivers of water, that bringeth forth his fruit in his season, his leaf also shall not wither, and whatsoever he doeth shall prosper.”

My father was home and I am my father’s son. My home is now within me. I shall carry it with me all my days and it shall give me strength. My children shall live in that home and they shall flourish in its wisdom, which will illuminate their paths through me, as my father’s father illuminated mine. In the words of Proverbs 17:6: “Children’s children are the crown of old men; and the glory of children are their fathers.”

Now begins my father’s long journey into memory. I know he has the strength, for this journey will last generations, from my children to my children’s children to the children I will never know. I hope to join him on that journey someday. For my family, for my mom, I end with this poem, which says, I think, what my father would say:

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost Whose woods these are I think I know. His house is in the village, though, He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow. My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year. He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound’s the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake. The woods are lovely, dark, and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep.

Miss you, Dad.